The Automatic External Defibrillator

The Automatic External Defibrillator

In 1978, the first portable Automated External Defibrillator (AED) was designed. This was the first design which allowed the AED to be used in emergency cases by minimally trained people. Since then AEDs have been researched and evolved into extremely light, user-friendly equipment that can be used anywhere, by anyone.

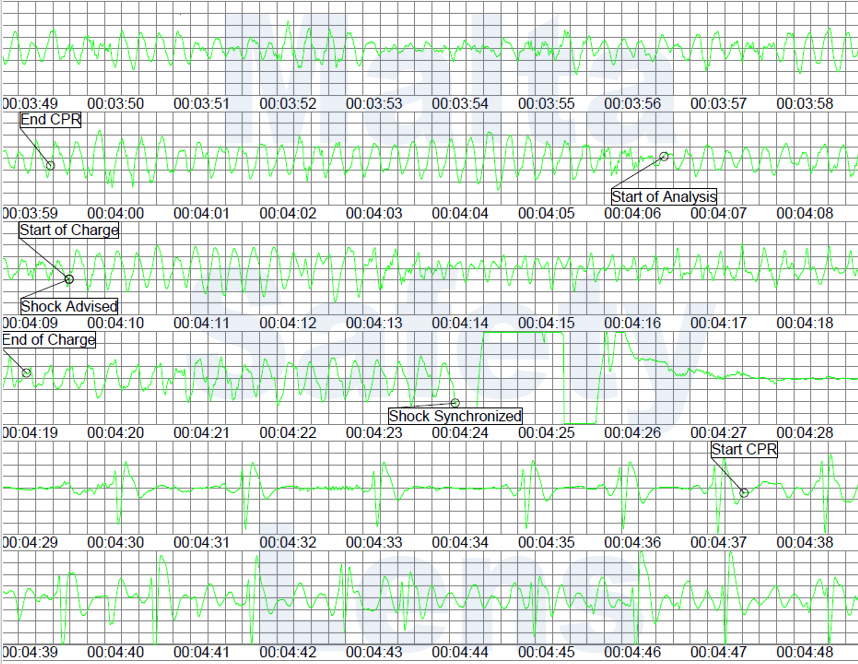

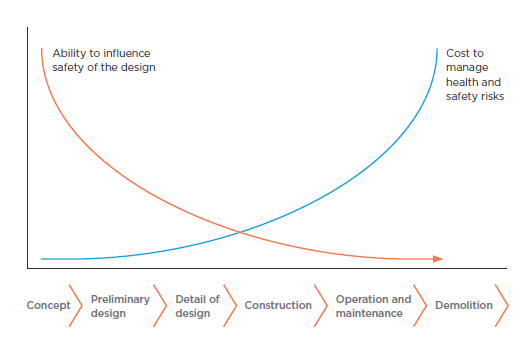

AEDs automatically detect whether the person (in layman’s terms) is alive, provide CPR instructions and decide on the provision of a shock. When the AED is used within a minute of the cardiac arrest, the survival rate is 90%. However, time is of the essence as the survival rate decreases by 10% every minute. Furthermore, it records the data and heart rhythms at the time of its use, assisting medical practitioners in the diagnosis of any heart conditions which may be present.

AEDs in Malta is becoming more popular. Local councils, clinics, schools, football grounds and shopping Malls are some of the sites which are most likely to have an AED.

An application called “AED Malta”, shows a number of AEDs which has been registered with the NGO running the application. The application shows the location of the nearest AED in your position.

Subsidiary legislation 424.13, regulates the requirements of first aid at the workplace in Malta. This legislation is quite simple, outlining the need for first aiders, a first aid room and first aid boxes, all depending on the number of workers employed. However, there is no mention of AED requirements. The decision to implement one is up to the company’s discretion and the H&S practitioners managing the safety provisions at the workplace.

We spend 8 hours a day at work, not at places of service and recreation, that’s one-third of our lifetime. And where we need it most, the AED might not be readily available.

It is a significant investment to procure the AED, train the personnel to use it and upkeep both the training and the equipment. However, I believe it is more important when a person survives an emergency requiring its use and returns home.

The following picture is data extracted from the use of an AED, showing the moment when regular heart rhythm was established by delivering CPR and using the AED following a sudden cardiac arrest caused by an irregular heartbeat. I was involved in this event, and within 5 minutes, due to the availability of the AED, and trained personnel, we were able to save this person.

I am sharing this information to raise awareness of the importance of AEDs at the workplace, and to show that they do actually save lives.

Doesn’t the above event justify the investment in an AED or several AEDs in bigger workplaces?

Put forward the idea to management, share this event, get approval, and have one at your workplace. Hope the need for it never arises, but if it is required, it’s invaluable to have one.

“L-Immaniġjar tal-Bidla”

“L-Immaniġjar tal-Bidla”

Good Father of the Family

Good Father of the Family

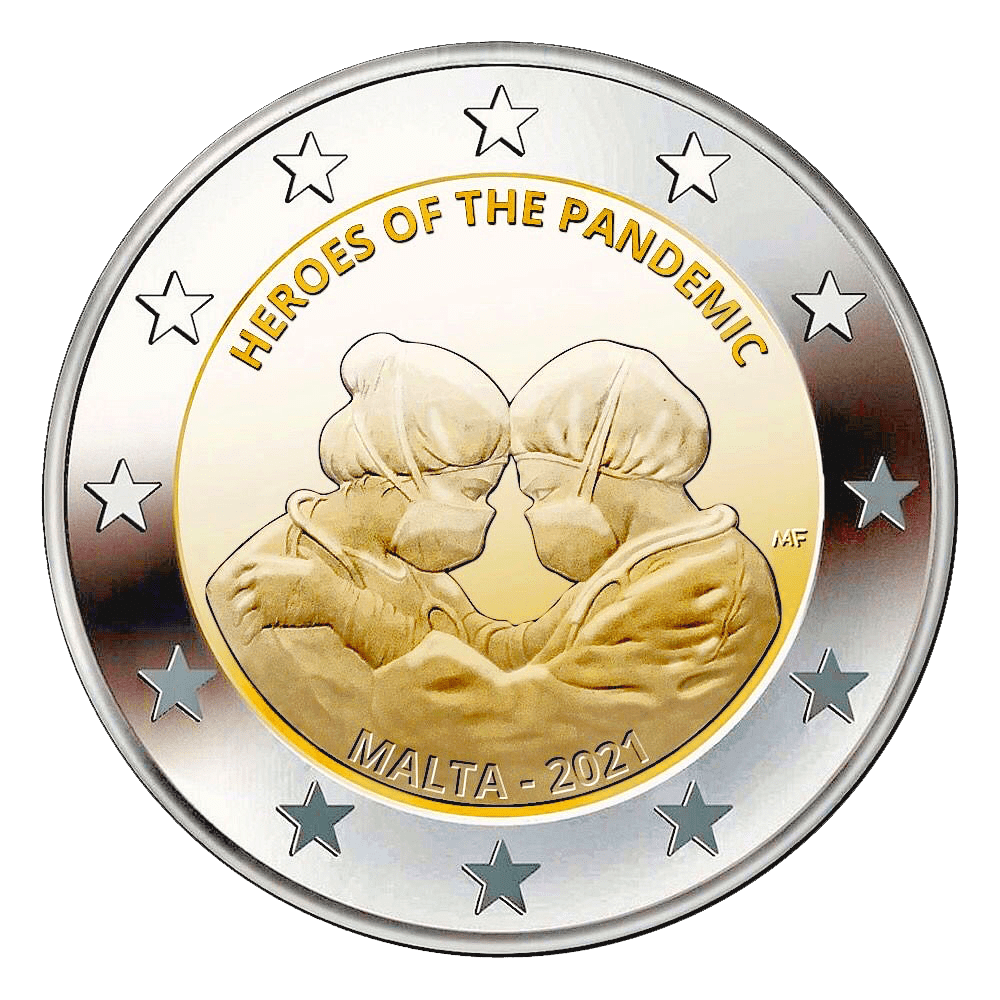

“L-Eroj Mhux Imsemmija”

“L-Eroj Mhux Imsemmija”