“L-Armar għall-Bini”

“L-Armar għall-Bini”

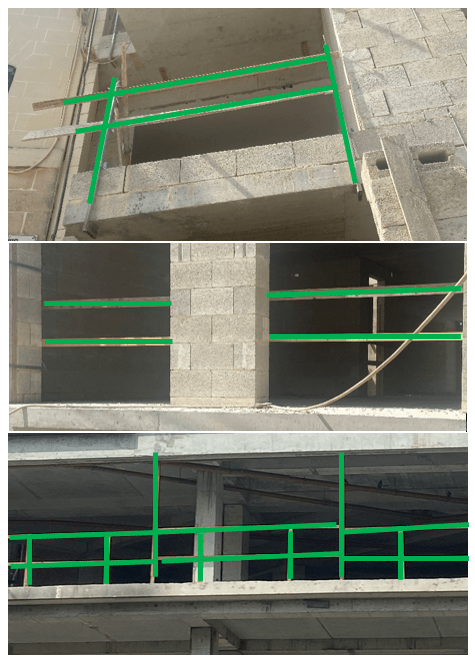

On the 2nd of May 2022, a video was posted online by a passerby of a scaffolding swaying with the wind, on the verge of falling onto the street causing damage to cars and possibly injuries to personnel.

Scaffolding is one of the most commonly used structures at construction sites. It is highly recommended to provide a safe working platform and avoid the usage of ladders and rope access techniques. But, it is only safe when it is built correctly.

An article published by the Times of Malta (timesofmalta.com) explains that the construction works on this historical building had conflicts with the law from the start, whereby works had commenced without approval from the planning authority. The planning commission fined the contractor 50 euros a day. Is that fine adequate to stop a contractor from carrying out illegal works?

Guidance and legislation are readily available, both locally, within the EU and from the Health and Safety Executive in the UK.

Legislation regulating the minimum requirement at construction sites (LEGISLATION MALTA) is extremely straightforward where scaffolding is concerned. The regulation states:

“All scaffolding must be properly designed, constructed and maintained to ensure that it does not collapse or move accidentally“

It is also stated that the scaffolding must be inspected and certified as safe for use, prior to being put into service, at periodic intervals and after any modification or exposure to bad weather.

The guidance from the OHSA (L-Armar għall-Bini (gov.mt)) goes one step further and determines the periodicity that the scaffolding is to be inspected and certified i.e. every week that it is in use.

Guidelines state that every scaffolding is to be secured to avoid any swaying. While, both the legislation and guidance provide information on ladders, gangways, guardrails and toe-boards that are to be installed with the scaffolding to ensure safe access and prevent falling tools.

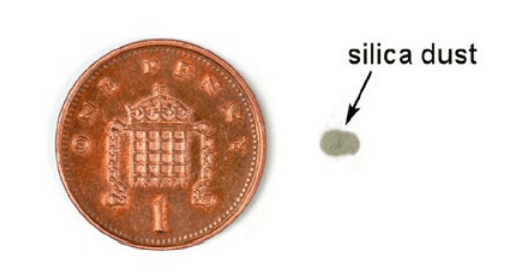

In the United Kingdom, scaffolding is regulated by the implementation of The Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015. Fines related to breaches in these regulations issued by the HSE range between 15,000 and 27,000 pounds. In Malta, the penalty for setting up inadequate scaffolding is only 250 euros as stipulated in the Occupational Health and Safety (Payment of Penalties) Regulations.

Since this video went viral, comments on social media read “unbelievable, health and safety doesn’t exist“, “Never ending story” yet again we only see public complaints when things are about to go south.

The posts that reach the attention of the mainstream media are mainly reactive to accidents and not proactive to ongoing health and safety concerns.

However, how many instances like this do we need to witness for the competent authorities to have allocated the adequate human resources to properly regulate the ever-growing construction industry?

Are the current fines adequate to promote a preventive culture rather than a corrective one and isn’t the preservation of human life more of an incentive than any fine imposed?

I write these posts not to point fingers, as it is never the objective of a health and safety practitioner to ascertain blame but to possibly provide insight into health and safety legislation and good practice.