“L-Immaniġjar tal-Bidla”

“L-Immaniġjar tal-Bidla”

Articles, blogs, entrepreneurs and business leaders all state that change is required for a company to grow and maintain a competitive edge against its competitors. Changes may occur in the product being provided, the company’s branding, management of people and technological changes. Such changes can promote the company’s profits, increase employee engagement and growth, and lead to a safer workplace. However, they can also lead to uncertainty, additional financial costs, reduced performance and the introduction of new hazards and risks.

The effectiveness of a change depends entirely on the management of the said change.

Management of change is a process by which the changes are systematically analysed to identify inherent environmental, health, safety and business risks which may be introduced in the process of implementation. It is so important in health and safety that it is an identified clause required to be implemented for ISO45001 Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems certification. Furthermore, although not mentioned directly in legislation, the General Provisions for Health and Safety (S.L. 424.18), places an obligation on the employer to evaluate the risks arising from equipment, chemicals, work processes and the workplace. As such, it can also be said that a procedure for the management of change helps the employers stay compliant.

Management of the change process would usually involve the following steps:

- A request for a change

- An evaluation of risks and hazards related to the change

- An evaluation of compatibility with current work equipment, infrastructure, chemicals and work processes.

- Identification of any changes required

- Training on the change and

- Implementation

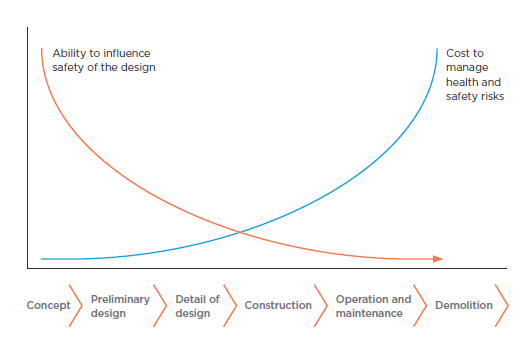

A concept which goes hand in hand with “Management of Change” is “Safety by Design”. Which, as defined by Worksafe is “the process of managing health and safety risks throughout the lifecycle of structures, plant, substance or other products”, perfectly illustrated in the picture below.

Should a change not be managed correctly, and safety not be given importance at the designed stage, the costs to remedy the risks introduced and the possibility of harm increase significantly.

When considering environmental, health and safety, quality and business requirements, change is not a matter of procuring and implementing equipment. It requires time, careful planning and proper evaluation. The personnel leading the change must make sure that the following pitfalls are avoided:

- Lack of communication and consultation with the stakeholders who may be affected by the change

- Tackling a big or several small changes all at once without the adequate resources

- Think that the change will affect only its immediate surroundings, without giving due consideration to secondary equipment, processes, legislative and standard requirements.

- Beliving that the change has been fully implemented, without proper long-term monitoring of its effectiveness.

In today’s fast-paced industry, change is no longer optional to stay ahead within your sector but is most often imposed by legislative changes, technology advancements and stakeholder requirements. As such, having a robust system to manage such changes is as important as any other day-to-day procedure required to keep the company afloat.